Guidelines for Ethical Research on Human Remains

Given by the National Committee for Research Ethics on Human Remains (Human Remains Committee) in 2022 (4th edition).

Download the guidelines as pdf.

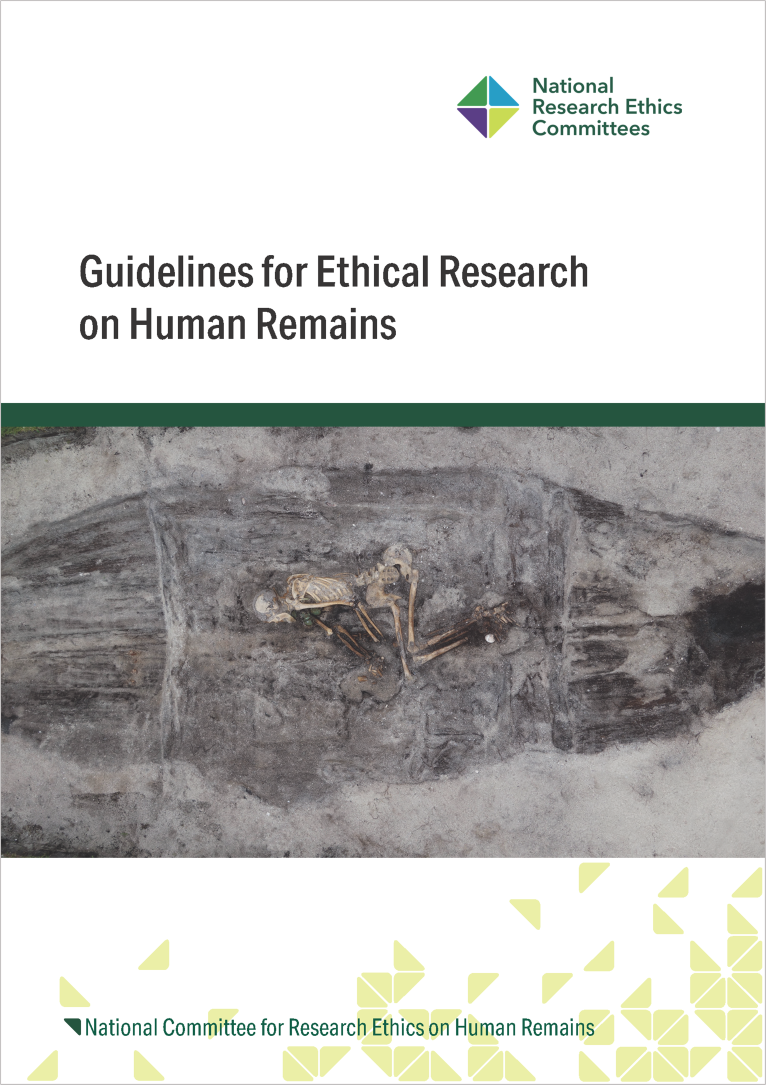

About the cover photo:

The photo shows a richly equipped Norse boat grave and the skeletal remains of a woman, aged 40–50. The gravesite was located at Hillesøy in the Municipality of Tromsø and dates to 770–840 CE. The grave and remains were investigated by the Arctic University Museum of Norway in 2018. Photo by Anja R. Niemi, Arctic University Museum of Norway.

Preface

The National Committee for Research Ethics on Human Remains (Human Remains Committee) is an independent and interdisciplinary committee of the National Research Ethics Committees (FEK) in Norway. The Human Remains Committee prepares and revises ethical guidelines for research on human remains.

Guidelines for Ethical Research on Human Remains is a dynamic document that should be revised as required in order to remain updated in accordance with any ethical issues researchers, institutions and others may encounter. The guidelines were first published by the Human Remains Committee in 2013 and translated into English in 2014. The cover photo was changed in 2016 and in 2018 the title of the Norwegian version was changed.

This version, which is the fourth, is the result of an extensive review process. In a meeting held on December 3rd, 2020, the Human Remains Committee decided to revise the guidelines. The working group responsible for the review, comprised of committee members, prepared several drafts, which were discussed by the committee at large beginning in January 2021. The final revised draft was then submitted for public consultation on November 1st, 2021, with February 1st, 2022, as the deadline for comments. 16 responses were received from research institutions, researchers and others with a connection to the field. All comments were discussed in detail by the working group and the committee. The final version of the guidelines was reviewed and adopted by all committee members in June 2022.

In the revision work, the committee placed particular emphasis on structure and framework, as well as how various factors, such as the Research Ethics Act, open science, Big Data and increased focus on repatriation, affect the guidelines. It has also been a priority to clearly emphasize research ethics as a foundation for good research on human remains. The most prominent change is a reorganization of the guidelines into two parts: «Part A: Recognition, consideration and context» and «Part B: Analyses, results, dissemination and repatriation», and the introduction of four new articles: destructive methods and verifiability (article 8), data management (article 9), repatriation (article 10) and visual dissemination (article 11). In addition, an introduction and appendix have been added.

The Human Remains Committee would like to thank all those involved for their feedback and collaboration in connection with the revision of these guidelines.

Oslo, August 2022

Sean D. Denham (Chair), Therese Robertsen Almaas, Marianne Hem Eriksen, Siri Forsmo, Kjetil Fretheim, Elin Rose Myrvold, Jens Rytter, Asgeir Svestad, Torgeir Sørensen, Sølvi Vik and Lene Os Johannessen (Secretariat).

Nils Anfinset (Committee Chair 2016–2021) and Tone Druglitrø (committee member 2020–2021) participated in revisions in 2021.

Introduction

The Guidelines for Research Ethics on Human Remains are based on recognized standards of research ethics within the research community. The guidelines are advisory, and their purpose is to invite reflection on and assessment of ethical issues relating to research on human remains (human biological material). Ethical reflection, wherein various considerations and principles are weighed against each other, should be an integral part of all research on human remains and present in all stages of the research process – from the planning of a project to publication and dissemination.

Research ethics[1]

Research ethics are applied ethics, based on a core set of scientific norms and values within the research community. These norms define the distinction between right and wrong, good and bad, acceptable and unacceptable. Ethical norms are not immutable, but rather adapt to reflect larger social trends. Thus, they require constant reflection and discussion.

Some of these norms are expressed through sound scientific practices, tied to the pursuit of accurate, adequate and relevant knowledge. These include originality, transparency and reliability. Other norms, such as responsibility, impartiality and criticism, regulate the research community and the relationships between researchers. These two sets of norms aim to protect the quality and integrity of research.

Another set of norms speaks to the relationship between the researcher and individuals and groups who participate in research, and seeks to ensure that the research is responsibly executed. These norms are based on principles of respect for human dignity, freedom and self-determination, protection from the risk of harm and undue pressure, and fairness in procedures and the distribution of benefits and burdens.[2] Research ethics are also based on the principle that research should benefit society and not cause harm to people, society, nature or the environment. Transparent and honest research dissemination plays a key role in this.

Research ethics entail the discussion and a balancing of these sets of norms within the research community. As such, research ethics build a framework for norm-based self-regulation.

Target groups and responsibilities

Researchers have an individual responsibility to familiarize themselves with the norms of research ethics and for ensuring that their research activities are conducted in accordance with these norms at all stages in the process.[3]

Research institutions have a responsibility to «ensure that research conducted at the institution complies with recognized norms of research ethics.»[4] Among other things, this includes a responsibility to train students and staff, and to ensure that all persons who carry out or participate in research are familiar with recognized ethical norms. Institutions have a special responsibility to uphold research ethical norms in a general sense. In terms of the scope of these guidelines, this entails ensuring that sound procedures for research on human remains are established, that any partners have similar procedures in place, and that any research activities being carried out have been coordinated with partners and any other ongoing or planned projects.

These guidelines are primarily aimed at students and researchers who will be carrying out research on human remains, but they may also be relevant for other forms of knowledge production. As an example, the guidelines may be used in reflection and self-assessment in connection with exhibitions, repatriation and the handling of human remains in cultural heritage management. It will be up to the research communities and institutions to clarify where these guidelines shall apply.

Both Norwegian and foreign legislation and administrative regulations have formal requirements for the excavation/collection, handling, sampling and analyses of human remains.[5] These systems help ensure that the management of and research on human remains take place within a sound framework. This is why it is also an ethical responsibility to familiarize oneself and comply with relevant laws and regulations. However, these guidelines presented here serve a different purpose and function than legal statutes, in that they are based on research and research ethics. In research, ethics apply independently of legislation.

Human remains

In these guidelines, the term human remains is to be understood as intact skeletons, parts of skeletons, and other human biological material kept in museums and collections, or discovered as a result of archaeological and other investigations. The term may also be used to include human remains that have never been buried but have instead been kept in unburied coffins and sarcophagi.

On the one hand, human remains are a scientific resource that may provide us with knowledge of past societies and cultures. On the other hand, they are the material remains of individuals. Both as scientific resources and as representatives of individuals or groups, human remains are part of a greater whole (such as other burial contexts or practices or cultural contexts). They should therefore be considered in light of this greater context. Within this, there are several dilemmas of an ethical nature. Examples of contexts where research ethics are challenged include research on the remains of individuals belonging to a historically oppressed group, remains that are unique in a research context, or human remains with no clear discovery context, origin or ownership history.

Research on human remains spans many different specialist fields, such as anthropology, archaeology, genetics, medicine and paleobiology. For that reason, these guidelines are not tied to any field in particular. Instead, they aim to be relevant for a wide range of disciplines.

Guideline structure

The guidelines include 11 articles, split into two parts: «Part A: Recognition, consideration and context» and «Part B: Analyses, results, dissemination and repatriation». Part A focuses on considerations of individuals, descendants, groups, discovery context, origin and ownership history. Part B focuses on considerations of research quality, the use of destructive methods, data management, repatriation and visual dissemination. In addition, there is an appendix with information on relevant laws, regulations and procedures, as well as on the National Research Ethics Committees (FEK) and the National Committee for Research Ethics on Human Remains (Human Remains Committee).

Part A: Recognition, Consideration and Context

1. The individual

Research on human remains requires recognition of the individual and the individual’s remains, irrespective of the age and condition of those remains. In research activities, the remains and their context should be treated with discretion and dignity. Perceptions of what is respectful and dignified treatment of human remains will vary with time and location. Researchers should familiarize themselves with and have regard for cultural and social contexts, and relevant perspectives on death, bodies and the afterlife.

2. Living decendants

When the identity of the deceased is known, the general rule is to contact any living descendants for dialogue on examination of the remains and potential results. This communication must take place before any research activity is carried out. If possible, researchers should consider providing regular information throughout the process. The closer the remains are to present day descendants, in terms of relationship or time, the more important it is to contact those descendants. The responsibility for establishing contact and providing information rests with the researcher.

3. Contextually unique human remains

All human remains, irrespective of age, are unique and have intrinsic value. Research activities that entail the destruction of human remains should only be carried out if it can be justified, based on a comprehensive and thorough assessment.

In addition, some human remains are unique as research material due to their lack of contextual parallel. Research on such remains should be assessed specifically, and one should consider whether other, previously collected materials and/or data can be used to attain the research objective.

4. Discovery context, origin and ownership history

It is important that the researcher is aware of the provenance of the human remains, i.e. their discovery context, origin and ownership history. In some cases, non-human remains, such as clothing, grave goods or animal remains may be part of the discovery context, and these will be relevant for our understanding of the individual’s cultural and/or religious affiliation. In the overall assessment of the discovery context, it is important to consider both the human and non-human remains together.

Researchers and research institutions must not contribute to grave robbery, theft or the unlawful trade of human remains. Research on human remains of unclear, unknown or disputed provenance could entail that researchers are complicit in unlawful trade or unethical activity, for example, if the remains have been procured in a way that entails discrimination of or injustice against individuals or groups. The provenance of the remains must be assessed and clarified in order for the research to be ethical. Such an assessment must take into account the specific circumstances of the case, but the researcher cannot waive responsibility for this part of the research.[6]

5. Affected groups

Different groups have different practices for dealing with death and the dead. What is considered perfectly acceptable to one group, may be considered offensive by another. One group should neither project its ideals regarding treatment of the dead onto another group, nor trivialize that other group’s views as a means of justifying their own actions.

A group with a history of marginalization or oppression may be distrustful of outside researchers investigating its past. Such distrust may arise when research has previously been used, or abused, to justify and increase historical discrimination against the group. In addition, distrust may be caused by a fear of the group’s history being appropriated by outsiders. Some groups may also feel that research, or western scientific methods, are not an appropriate approach to investigating their history.

Research on individuals from indigenous peoples or historically oppressed groups is not necessarily unethical, but does require particular ethical awareness. Researchers should identify groups that may be affected by their research, familiarize themselves with the affected groups’ views and positions, and assess how best to address these through dialogue and/or involvement.[7] These considerations will vary from case to case and will depend on the context.

Part B: Analyses, Results, Dissemination and Repatriation

6. Research project quality and feasibility

All ethical reflection on research into human remains should include an overall assessment of the project, weighing up the potential deterioration/destruction of the remains and burden on the affected parties against the project’s quality and feasibility. Several factors may affect the research project’s quality and feasibility.

Among other things, researchers are encouraged to reflect on the following:

- Are the research questions accurate and appropriate?

- Are the chosen theories and methods appropriate for the research questions?

- Do those who will be performing the excavation/retrieval, sampling and analysis have the required expertise?

- Is the research project feasible with the resources available?

- Does the project have data management and publication plans?

- How will the methods – both destructive and non-destructive – be documented?

7. Unintended consequences

Research is often carried out for several purposes and can have consequences researchers did not pursue or anticipate. While some of these consequences may be considered desirable, others may be seen as problematic or unwanted. Researchers have a responsibility to consider and evaluate the various potential or likely consequences for each project.

8. Destructive methods and verifiability

The use of destructive methods[8] hastens the deterioration of the source material. Therefore, stringent documentation requirements should be imposed on all sampling, and the needs of other researchers should be taken into consideration. If the source material has been exhausted, it will necessarily rob other researchers of the opportunity to carry out research which requires that material.

It is also important to consider the verifiability of the research. In order to verify the results of an experiment, it must be possible to perform at least one additional analysis of the same source material. Researchers should therefore ensure that there is enough material left for future sampling.

The use of destructive methods should be subject to careful consideration. Research involving such methods should include a sampling strategy limiting the loss of material, appropriate and realistic analytical methods, and a plan for handling any unused sample materials. Open sharing of data could prevent or reduce future destruction of materials.

In a broader sense, considerations of human remains as unique research materials also entails recognition of research beyond one’s own project.

9. Data management

Anyone engaging in research on human remains should have a plan for how to manage their data, in terms of appropriate storage, organization, licensing and accessibility.[9] Good data management in research projects is important, among other things to ensure that the data can be shared, both nationally and internationally, to limit the destruction of materials, reduce pressure on collections and preserve the materials for future generations.

Good data management is especially important if the research makes use of analyses that produce large data sets, or if the research makes use of potentially sensitive data, such as genetic data. Good data management can be achieved, among other things, by using databases intended for this specific purpose, including international databases.

The project leader should clarify who is responsible for creating the data set, for example, a researcher directly associated with the project or an outside party. If an outside party is creating the data set, it should be clarified as to whether this partner is defined as a collaborative partner, or whether the work is performed as a contract service. This distinction is relevant for ownership and/or access to the data. One should also clarify how, by whom and in which format the data will be stored. Furthermore, one should clarify how and in which format the data will be made available, and how any sensitive data will be managed and protected. Examples of sensitive data include DNA data from groups that object to the public availability of representative genetic data and data derived from individuals of known identity.

10. Repatriation

In some cases, it may be appropriate to repatriate human remains, i.e. return them to the place or context they originally came from or are associated with. Repatriation may entail reburial or returning the remains to a suitable location or institution.

Reasons for repatriation include the remains representing a close relative of living individuals, their being affiliated with a marginalized group or their having been acquired by unethical means. Repatriation due to affiliation with a marginalized group or unethical acquisition should be undertaken in dialogue and collaboration with official representatives of the affected group and/or the relevant cultural heritage authorities. One must ensure that the repatriation is appropriate and takes into consideration the provenance and familial and contextual affiliations of the remains. If the origin or cultural context of the remains are unclear, one should consider preliminary investigations to determine these with more certainty. It is important that researchers and institutions are clear and thorough in their dialogue with affected communities, including both what is known and what is unknown about the remains. Such processes should be open and transparent.

If repatriation involves reburial, future research on the remains will not be possible. One consequence of this may be that certain groups lose an opportunity to learn more about their ancestors and history. To account for a group’s potential future interest in research, one could consider various options – such as osteological analyses, photographic documentation and/or sampling – in close consultation with the community of origin, before the remains are reburied.

11. Visual dissemination

Research ethics also apply to visual dissemination of human remains in physical and digital exhibitions as well as other forms of dissemination. Overall, visual dissemination of human remains should be based on academic considerations and included as a natural part of the purpose of dissemination – to present, learn or inform.

Human remains should be presented with dignity (see article 1) and in such a way that they take into consideration the interests of potential living descendants (see article 2), as well as ethnic, religious or other groups (see article 5). Exhibition of human remains of unknown or problematic provenance should be subject to special considerations (see article 4). Physical exhibition of remains may also cause the material to deteriorate. It is therefore important to ensure good conditions for preservation and presentation.

The responsible institution should have procedures in place for handling requests from individuals or groups for the removal of human remains from exhibits.[10]

We are also encouraging institutions to regularly discuss how human remains are used in exhibits and other dissemination, taking into account academic relevance, research ethics, knowledge dissemination and current social discourse, as well as public interests.

Appendix

Laws, regulations and procedures

If the research entails excavation of materials, one must be aware of and adhere to any legislation that protects graves and human remains. A summary of the distribution of responsibility between various cultural heritage management bodies in Norway can be found in Veileder til ansvarsforskriften.[11] See also Veileder ved funn av menneskelige levninger[12], which provides an overview of relevant legislation and current practices for handling human remains in connection with chance discoveries and finds in a cultural heritage management context.

If the research involves materials that are part of an institutional collection, one must contact the relevant institution to clarify their internal process. The material may be stored at a different institution from the one that has official responsibility for the remains, and in these cases one must contact the officially responsible institution to obtain permission. If the research will affect human remains protected under the Cultural Heritage Act, permission must be applied for.[13]

If the skeletal material is to be used in medical and health-related research, the research is subject to the provisions of the Health Research Act.[14] In these cases, a permit from the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK) is required for the project to move forward. See www.rekportalen.no for more information.

Research on Sami human remains

ILO Convention No. 169[15] grants indigenous status to the Sami people in Norway. The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples states that indigenous peoples have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions.[16] International law also establishes that indigenous peoples have the right to participate in decision-making processes and to be consulted in matters that affect them.[17]

In March 2021, the Plenary Assembly of the Sami Parliament adopted a report on the protection of Sami cultural heritage,[18] which will inform the direction of work with Sami cultural heritage for the years to come, including management of human remains and grave goods (ch. 6).

A special agreement has been negotiated between the University of Oslo (UiO) and the Sami Parliament regarding the management of Sami human remains in the Schreiner Collection at UiO.[19] The Sami Parliament has also adopted special ethical guidelines for medical research involving the Sami,[20] which also includes research on human biological material. Among other things, these guidelines regulate their right to co-determination and consent in connection with research.

In addition to a permit from the responsible institution, consultation with and consent from the Sami Parliament are required for research on Sami human remains.

National Research Ethics Committees

The National Research Ethics Committees (FEK) in Norway have statutory authority pursuant to the Research Ethics Act. FEK is the leading body for research ethics in the Norwegian national research system. FEK is comprised of the National Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (NEM), National Committee for Research Ethics in Science and Technology (NENT), National Committee for Research Ethics in the Social Sciences and the Humanities (NESH), National Commission for the Investigation of Research Misconduct, and National Committee for Research Ethics on Human Remains (Human Remains Committee). The three field-specific committees, NEM, NENT and NESH, were established in 1990, as recommended in Stortingsmelding no. 28 (1988–1989) Om forskning. In 2007, the three committees were included in the Research Ethics Act, and the National Commission for the Investigation of Research Misconduct was established. In 2008, the Human Remains Committee was established as an independent and advisory body in FEK.

The committees and commissions under FEK are independent and advise on research ethics issues. As of 1 January 2013, FEK became an administrative body under the Ministry of Education and Research.

National Committee for Research Ethics on Human Remains (Human Remains Committee)

The Human Remains Committee was established following a proposal from NEM and the board of the University of Oslo. The background for establishing the committee was the University of Oslo’s work on preserving and researching Sami material in the Schreiner Collection, and requests for the repatriation of a portion of these materials. The committee was originally established as a sub-committee of NESH, however it has been a separate, interdisciplinary committee in FEK since November 2021. NEM, NENT and NESH give the Human Remains Committee mandate, and appoint its members.

The Human Remains Committee provides guidance and advice to researchers, specialists, institutions and authorities on ethical issues related to research on human remains.

The committee prepares and revises guidelines and provides information, education and dissemination related to ethical issues in connection with research on human remains.

The committee can give opinions on/evaluations of research projects, education, visual dissemination, repatriation and handling of human remains in cultural heritage management and archaeological excavation. The only criterion is that the issue must concern research-related handling of human remains. Anyone (students, researchers, institutions, affected parties, etc.) can contact the Human Remains Committee, but the committee is free to determine which issues they choose to address.

In its activities, the committee takes into consideration ethical guidelines prepared by both national[21] and international bodies[22], as well as relevant provisions in current legislation, such as the Cultural Heritage Act[23], the Svalbard Environmental Protection Act[24], the Burial Act[25] and any international conventions to which Norway has acceded.[26]

The committee is comprised of ten members and one deputy member. Nine of the members are scientific experts from relevant fields – one member is a lay representative. In order to ensure legitimacy, the Human Remains Committee should also include members from each of the bodies granting its mandate, NEM, NENT and NESH. At least one of the members must have a background in research on Sami culture and society.

Human Remains Committee opinions

The Human Remains Committee has prepared opinions on many issues which give rise to various ethical questions in connection with research on human remains. These opinions may be useful in discussions and ethical reflections on one’s own research. You can read them here: https://www.forskningsetikk.no/om-oss/komiteer-og-utvalg/skjelettutvalget/uttalelser/

Former and current members of the Human Remains Committee

2022-

Sean D. Denham (Chair), Therese Robertsen Almaas, Marianne Hem Eriksen, Siri Forsmo, Kjetil Fretheim, Elin Rose Myrvold, Jens Rytter, Asgeir Svestad, Torgeir Sørensen (deputy) and Sølvi Vik.

2020-2021

Nils Anfinset (Chair), Sean D. Denham, Therese Robertsen Almaas, Tone Druglitrø, Marianne Hem Eriksen, Siri Forsmo, Kjetil Fretheim, Elin Rose Myrvold, Jens Rytter, Asgeir Svestad and Torgeir Sørensen (deputy).

2018-2019

Nils Anfinset (Chair), Therese Robertsen Almaas, Sean D. Denham, Siri Forsmo, Kjetil Fretheim, Tora Hultgren, Elin Rose Myrvold, Jens Rytter, Birgitte Skar and Unn Yilmaz.

2017

Nils Anfinset (Chair), Therese Robertsen Almaas, Dag Brusgaard, Sean D. Denham, Ingegerd Holand, Tora Hultgren, Elin Rose Myrvold, Jens Rytter, Birgitte Skar and Unn Yilmaz.

2016

Nils Anfinset (Chair), Dag Brusgaard, Finn Audun Grøndahl, Ingegerd Holand, Tora Hultgren, Jon Kyllingstad, Patricia Melsom, Ingrid Sommerseth, Birgitte Skar and Unn Yilmaz.

2013-2015

Anne Karin Hufthammer (Chair), Nils Anfinset, Dag Brusgaard, Finn Audun Grøndahl, Ingegerd Holand, Tora Hultgren, Jon Kyllingstad, Patricia Melsom, Ingrid Sommerseth, Birgitte Skar and Unn Yilmaz.

2012

Anne Karin Hufthammer (Chair), Dag Brusgaard, Ingegerd Holand, Tora Hultgren, Jon Kyllingstad, Patricia Melsom, Ingrid Sommerseth, Birgitte Skar and Unn Yilmaz.

2011

Oddbjørn Sørmoen (Chair), Dag Bruusgaard, Marit Anne Hauan, Ingegerd Holand, Anne Karin Hufthammer, Jon Kyllingstad, Patricia Ann Melsom and Ingrid Sommerseth.

2008-2010

Oddbjørn Sørmoen (Chair), Hallvard Fossheim, Marit Anne Hauan, Ingegerd Holand, Anne Karin Hufthammer, Jon Kyllingstad, Patricia Ann Melsom (f.o.m. 2009), Ingrid Sommerseth, Åge Wifstad and Finn Ørnulf Winther.

Notes

[1] This section is based on the presentation in Guidelines for Research Ethics in the Social Sciences and the Humanities. National Committee for Research Ethics in the Social Sciences and the Humanities (NESH), 2021, p. 6–7.

[2] The principles of sound research were defined in The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research. Bethesda, Md.: The Commission, 1978.

[3] Section 4 of the Act relating to ethics and integrity in research (Research Ethics Act).

[4] Section 5 of the Act relating to ethics and integrity in research (Research Ethics Act).

[5] See appendix for more information on laws, regulations and procedures. See also Veileder ved funn av menneskelige levninger. National Committee for Research Ethics on Human Remains (Human Remains Committee), 2018.

[6] See also article 33 in the Guidelines for Research Ethics in the Social Sciences and the Humanities. National Committee for Research Ethics in the Social Sciences and the Humanities (NESH), 2021.

[7] See the section «Research on Sami human remains» in the appendix.

[8] Some methods that are considered non-destructive, such as radiography or synchrotron imaging, may cause damage to biomolecular materials, such as proteins or DNA. It should therefore be standard practice to record the material’s accumulated exposure to radiation.

[9] For national guidelines, see National strategy on access to and sharing of research data. Government, 2017, and The Research Council of Norway’s Policy for Open Access to Research Data. Research Council of Norway, 2017. As additional support in the preparation of a plan for data management, we refer to the FAIR principles (Wilkinson, M., Dumontier, M., Aalbersberg, I. et al., “The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship”. Sci Data 3, 2016), for example, how they have been implemented by GO FAIR.

[10] For a more generalized framework for museum and exhibition work, see Code of Ethics for Museums. International Council of Museums (ICOM), 2017.

[11] Veileder til ansvarsforskriften. Directorate of Cultural Heritage, 2020.

[12] Veileder ved funn av menneskelige levninger. National Committee for Research Ethics on Human Remains (Human Remains Committee), 2018.

[13] Retningslinjer for prøvetaking og vitenskapelig analyse av kulturhistorisk materiale i universitetsmuseenes samlinger. Felles kvalitetssystem for universitetsmuseene, 2018.

[14] Act no. 44 of 20 June 2008 relating to medical and health research (the Health Research Act).

[15] ILO Convention no. 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries. Geneva, 1989.

[16] UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Article 31. UN General Assembly, 2007.

[17] ILO Convention no. 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries, article 6. Geneva, 1989; UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Articles 12, 18, 19 and 32. UN General Assembly, 2007; UN Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, article 27. UN, 1976.

[18] Áimmahuššan – Sametingsmelding om samisk kulturminnevern. Sami Parliament, 2021.

[19] Avtale mellom Universitetet i Oslo og Sametinget om forvaltningen av samiske levninger ved Universitetet i Oslo (De Schreinerske Samlinger), 2020.

[20] Etiske retningslinjer for samisk helseforskning. Sami Parliament, 2019.

[21] Guidelines for Research Ethics in the Social Sciences and the Humanities. National Committee for Research Ethics in the Social Sciences and the Humanities (NESH), 2021. Guidelines for research ethics in science and technology. National Committee for Research Ethics in Science and Technology (NENT), 2016. Etiske retningslinjer for samisk helseforskning. Sami Parliament, 2019.

[22] For example Code of Ethics for Museums. International Council of Museums (ICOM), 2017.

[23] Act no. 50 of 9 June 1979 relating to Cultural Heritage (Cultural Heritage Act).

[24] Act no. 79 of 15 June 2001 relating to the Protection of the Environment in Svalbard (Svalbard Environmental Protection Act).

[25] Lov 7. juni 1996 nr. 32 om gravplasser, kremasjon og gravferd (gravferdsloven).

[26] Such as the UNESCO Convention on the means of prohibiting and preventing the illicit import, export and transfer of ownership of cultural property. Paris, 1970; UN Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Article 27. UN, 1976; ILO Convention no. 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries. Geneva, 1989; European Convention on the Protection of the Archaeological Heritage. Valletta, 1992; European Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities. Strasbourg, 1995; UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Articles 12, 18, 19 and 32. UN General Assembly, 2007.