Are we not evil after all?

The two most famous social psychology experiments in history revealed the underlying evil of human beings – or did they? Several quarters now claim that the scientists who achieved world fame manipulated the results.

This article was first published in Norwegian on March 22, 2021

How could the holocaust happen, how did the Nazis get enough people to work in the extermination camps?

‘No problem, you can find them in any small town in America’, believed Stanley Milgram, a psychologist at Yale University. Milgram conducted the Obedience to Authority Experiment (see fact box) and emerged as the leading light in the field of psychology. It was not until Philip Zimbardo conducted his Stanford Prison Experiment ten years later (see fact box) that Milgram was faced with a competitor who could challenge his standing.

In the United States, even today, it is difficult to find elementary psychology books that do not cite one or both of these experiments.

The experiments by Milgram and Zimbardo received considerable criticism for exposing the research subjects to extreme mental stress and duping them. Such experiments would not have been possible under current ethical guidelines, but in recent years, more and more people are also questioning the conclusions drawn by the two psychologists.

Piles of archival material

Obedience to Authority

- When: 1961

- Head of research: Stanley Milgram, 1933–1984

- Research subjects: several hundred random people from New Haven, Connecticut

- Hypothesis: we obey orders even if if entails inflicting pain on others.

- Method: the research subjects were ordered to administer electric shocks to another person. They were not informed that the shocks were not real.

Australian Gina Perry has spent years of her life unravelling Milgram’s experiments. In 2012, she published the book Behind the Shock Machine: The Untold Story of the Notorious Milgram Psychology Experiments. What amazed the psychologist and research historian the most was that no one else had thoroughly reviewed the raw material from experiments that had such importance. And what about the research subjects? Few people had spoken to them.

Gina Perry ploughed through piles of archival material and hours of audio recordings. She also tracked down several of the experiment participants and became steadily more convinced that Milgram did not actually test his hypotheses, but sought to confirm them.

Electric shocks shocked the world

Stanley Milgram duped the research subjects into believing they were part of an experiment to investigate whether a student would learn faster when he was given an electric shock every time he gave an incorrect answer. In fact, the electric shocks were not real and the student was an actor.

The person who was told to administer what he believed to be an electric shock was the real research subject. The purpose was to investigate whether people obeyed orders even if it entailed inflicting pain on others.

What shocked the world was that two out of three research subjects obeyed orders all the way up to the strongest current of 450 volts. It is this result that is cited every time the experiment is referenced. Gina Perry believes that the reality of the situation is far more complex.

Shakes, sweat and tears

Milgram conducted a number of variations of the experiment, and the high rate of obedience he achieved only happened when the student was sitting in another room. In contrast, when the student was moved to the same room as the person giving the ‘shocks’, 60–70% of them disobeyed orders. More than 20 variants of the experiments were conducted in total, and in more than half of them, over 60% of the research subjects disobeyed orders.

Moreover, only half of the students were convinced that the shocks were real, and among those, only one in three obeyed orders. The audio recordings also show that the participants suffered considerable anguish, and were protesting, crying, sweating and shaking.

Gina Perry believes the results could just as easily be interpreted to mean the opposite of what Milgram claimed they proved: that they are evidence that we disobey orders.

Sadistic students?

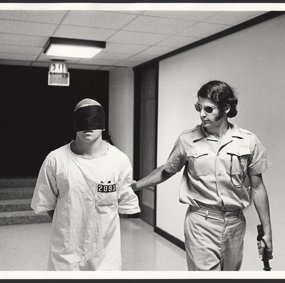

In the summer of 1971, Philip Zimbardo, a psychology professor, converted a basement of Stanford University into a mock prison. Twelve students were given the role of prison guards, 12 of prisoners. All were men. The purpose was to see if the guards developed sadistic tendencies, which they did. Zimbardo claimed to show that we all have a sadist in us who only surfaces when the circumstances are right.

According to Zimbardo, the prison guards were given free rein to develop their own methods. However, a series of interviews with the ‘prison guards’ and more recent reviews of the archival material and audio recordings from the experiment give a completely different picture. Before the experiment began, Zimbardo urged the guards to frighten the prisoners.

Stanford Prison Experiment

- When: 1971

- Head of research: Philip Zimbardo, 1933–

- Research subjects: 24 male students

- Hypothesis: we develop sadistic tendencies if we are given unlimited power over other people.

- Method: half of the students were given the role of prison guards, the rest the role of prisoners.

Several of the guards have since claimed that they thought the aim was to see how quickly the prisoners could be broken down, and that their task was therefore to devise methods to expedite this process. They also received instructions from the researchers about which methods they could use. One of the guards was reprimanded for not being tough enough on the prisoners. In contrast, the guard most feared by the prisoners was praised by Zimbardo, who thanked him for doing such an excellent job.

Attempts to repeat the experiment without any instructions to the guards have not led to sadistic behaviour, rather the opposite; the guards and prisoners have become good friends.

Zimbardo has said that he is tired of defending the experiment. He points out that despite the controversy, its is the most well-known study in the history of psychology. Now 87 years old, Zimbardo believes that the best defence of the study is its longevity.

Chasing fame

Professor Hank Stam of the University of Calgary is critical of the early social psychology experiments. He believes that Stanley Milgram did not disclose the finding that the research subjects disobeyed orders because he ‘knew what success looked like’.

Because who would have heard of Milgram and Zimbardo if their conclusions had been that most people are wary of following orders and do not exploit situations where they can humiliate and harass others with impunity?

According to Rutger Bregman’s book Humankind: A Hopeful History, the world’s two best-known social psychology experiments do not expose our underlying evil; they are just stories of psychologists who yearned to be famous.

Sources: Stanley Milgram: Obedience to Authority, Gina Perry: Behind the Shock Machine: The Untold Story of the Notorious Milgram Psychology Experiments, Rutger Bregman: Humankind: A Hopeful History, Thibault Le Texier: Debunking the Stanford Prison Experiment (APA), Philip Zimbardo: The Lucifer Effect

Translated from Norwegian by Carole Hognestad, Akasie språktjenester AS.