Journal editor: – A lie can travel around the world in a few hours

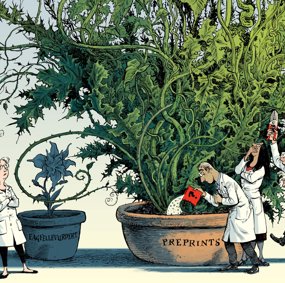

Publishing preliminary findings can lead to researchers making important corrections. But credibility is compromised when the scope explodes and incomplete research is spread in all channels.

This article was first published in Norwegian on October 11 2021.

Posting research online before it is peer reviewed is nothing new, but in the field of medicine, this practice only started about five years ago. The volume increased rapidly with the pandemic: according to a review published on the website github.com by librarians Nicholas Fraser and Bianca Kramer, more than 50,000 preprints about COVID-19 were posted online in the period January to May 2020.

Preprint

A preprint is a non-peer-reviewed manuscript that has been uploaded to an open online platform. The purpose is to give the public quick access to findings, enable researchers to take greater ownership of the idea, and receive constructive criticism from colleagues.

Source: the article entitled ‘Preprints are here to stay’ by Ragnhild Ørstavik

Alarm bells are ringing. Is the credibility of research at risk?

‘It’s possible that preprints can compromise credibility. There is limited quality control, and it can be difficult for lay people to understand the difference between a preprint and a peer-reviewed article’, says Daniel Quintana, researcher at the Department of Psychology, University of Oslo.

However, he believes that the advantages outweigh the disadvantages. He himself is an avid user of preprint platforms: he posts drafts of research articles, receives feedback, makes corrections and then reposts.

‘Preprints have really improved my work and workflow.’

Kerfuffle over vitamin D

Preprint platforms are websites where researchers can post their work before it has been peer-reviewed. Some of the platforms are linked to journals, such as The Lancet’s ‘Preprints with The Lancet’.

The problems arise when incomplete studies are taken out of context, which is exactly what happened with a study that was published in Preprints with The Lancet in the winter of 2021. The article claimed that treating COVID-19 patients with activated vitamin D (caldifediol) could reduce the number of deaths by 60% and the number requiring intensive care by 80%.

David Davis, a member of the British parliament, described this study as ‘very important’ in a Twitter post. In a later Tweet, he called on the UK to immediately start using this medicine. The study was widely reported internationally, including by the national Norwegian broadcaster, NRK.

However, the comments field on the preprint platform was quickly bombarded with critical questions, particularly about whether this was really a randomised trial as claimed by the researchers. After an investigation, the journal decided to remove the article from its website and post an explanation.

The study was also submitted to The Lancet for peer review, but was rejected.

Still being shared

John McConnell, editor of The Lancet Infectious Diseases, discussed the episode at the World Conference on Research Integrity in June.

‘Although we have removed the study, it continues to attract attention. People are still re-tweeting David Davis’ original Twitter post. The full-text version of the study has been viewed nearly 160,000 times, and the study continues to receive media coverage’, McConnell said.

He went on to say that, by June, the link to the study had been tweeted or re-tweeted nearly 26,000 times. It had also been referred to as ‘published in The Lancet’, when in reality The Lancet had not carried out any quality control beforehand.

‘It is said that a lie can travel around the world in a few hours while the truth is still lacing up its boots. I think we’ve seen a lot of that over the last 18 months’, McConnell said.

Both McConnell and Daniel Quintana emphasise that even a peer review does not provide any guarantee.

‘A poorly peer-reviewed study can create even more problems for the credibility of research in the long term’, Quintana believes.

However, McConnell notes that preprints exacerbate the problem. During the conference, he questioned whether the preprint platforms will survive the pandemic.

No control over proliferation

Ragnhild Ørstavik, assistant editor-in-chief of the Journal of the Norwegian Medical Association, is also concerned. She points out that the intention with preprints was for the discussion to take place on the preprint platforms.

‘But much of the discussion has now moved to social media, where you don’t have any control over the proliferation of research results. In addition, the mainstream media select items from the preprint platforms and publish them as news.

‘How can we counter this?’

‘I think we need to act before the results have spread. It must be made more apparent that these results are more uncertain than others.’

She believes that whoever conveys the news also has a responsibility to convey the uncertainty – if the news is to be conveyed at all. She also believes that the scientific method and quality assurance of research should be taught at school.

‘But it’s a difficult goal to achieve, so I think that the responsibility lies primarily with the journalists and researchers who bring the news to light.’

Ørstavik refers to the special circumstances of the pandemic. Under other circumstances, there would be less urgency, and she believes that caution should therefore be exercised in non-pandemic situations when communicating preliminary results.

‘In addition, journals need to understand the importance of reducing manuscript processing times.’

Uncertain long-term effects

Karin Magnusson is a researcher at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH) and co-author of two preprints that have attracted considerable attention. One of the preprints was about the long-term effects of COVID-19. According to this study, which has not yet been peer-reviewed, the long-term effects are not as bad as implied by the media.

‘Publishing preliminary findings may be more ethically correct than keeping the knowledge to yourself for a long time’, she believes.

Magnusson is of the opinion that the long-term effects of COVID-19 are something that decision-makers need to be informed of straight away as this information helps to determine political measures.

However, a colleague contacted her some time ago and mentioned that she had written about a preprint on Twitter. He wondered what she thought about preprints.

‘There are probably a lot of people who are concerned about this, especially the older generation’, says Magnusson.

In general, she believes that preprint publication contributes to transparency in research. She explains that everyone can get involved and provide input, and it can improve the quality of research.

Extra demands on researchers

Magnusson also believes that the urgency caused by the pandemic has meant that she and her colleagues are even more thorough in the early stages of the research process. Numerous versions of articles have been circulated internally at NIPH in order to obtain critical input. Internal forums have been used more often than usual when it comes to methodology and the linking of large register databases, which she herself works with.

‘When you’re going to publish results in preprints, and you know that many people are interested and that there might be media coverage, it puts extra demands on researchers at an early stage’, points out Magnusson.

Moreover, she and her colleagues are always open about the fact that the results are not peer-reviewed.

In order to make the preprint results known, they have mainly published the results on NIPH’s website. However, the results on long COVID were first sent to a selected medium.

‘We wanted to ensure that the results showing the limited long-term effects of COVID-19 received publicity. After all, the media has a tendency to only write about studies with alarming results.

Mentioned in the last sentence

The Aftenposten newspaper was the first to write about the subject, under the heading ‘Norwegian study with 2 million people: most do not get long COVID’.

‘The fact that it was referring to a preprint was not mentioned until the last sentence of the main body of text. Do you think that’s good enough?’

‘Yes, I think it’s sufficient to mention it somewhere in the text. Popular science articles need to be short and concise. But we as researchers can certainly encourage the media to briefly describe the difference between a preprint article and a peer-reviewed article.’

Magnusson also points out one of the strengths of NIPH’s data material: NIPH’s results are based on the Emergency Preparedness Register for COVID-19, which consists of data retrieved from a number of Norwegian registers. The preparedness register contains data on two million people.

‘Although our findings are preliminary, we know that we have good-quality data and that we have used suitable methods, and we have a responsibility to share our findings.’

Putting things right

What responsibility do researchers really have when inaccurate research results are disseminated among the population? Should they publicly correct their own or other people’s results?

‘If I had submitted a preprint about a drug to combat COVID-19 that later turned out to be ineffective, I would feel a responsibility to let people know’, says Ragnhild Ørstavik.

Ethical guidelines

According to the guidelines of the National Research Ethics Committees, researchers

1) must strive to point out any risk and uncertainty factors that may have a bearing on the interpretation and possible applications of the research findings

2) may share hypotheses, theories, and preliminary findings with the public while a project is ongoing, but (…) be cautious about presenting preliminary results as final results

Sources: Guidelines for Research Ethics in Science and Technology (Section 1) and Guidelines for Research Ethics in the Social Sciences, Humanities, Law and Theology (Section 2)

Daniel Quintana agrees. He believes that, depending on what the error relates to, the researcher should either rectify it and give details on the preprint platform or remove the entire study.

‘One of the good things about preprints is that it’s much easier to correct mistakes. Once a study has been published, it’s more difficult.’

‘But what if the results have already been disseminated to the public?’

‘It’s difficult, because things spread quickly. But you should try to fix it. If a journalist has written about it, you can contact that person.’

He also thinks that the researchers themselves should have a public platform, such as a blog or an open account on social media. He suggests that TikTok or Instagram can be used when researching a topic that concerns young people. You can also use these platforms to inform the public of any errors in your own research.

‘Would you have a responsibility if it concerned another researcher’s results?’

‘If I discovered something, I could let them know and attach a link. It doesn’t take much effort. But I don’t think we are responsible for looking for other people’s mistakes. However, we need to be thorough in our own work.’

International guidelines

ASAPbio is a scientist-driven, non-profit organisation that promotes transparency and innovation in life science communication. In 2020, it conducted a survey about preprints among groups such as librarians, researchers and journalists. The results showed that people’s main concern was the possibility of premature media coverage.

Since the survey, ASAPbio has proposed some guidelines for communication about preprints, as part of the Preprints in the Public Eye project.

In the guidelines, they encourage researchers to explicitly state that the results have not been peer-reviewed. They should also try to present the research in a way that the findings cannot be misinterpreted, and they should not exaggerate the significance of the findings.

The journalists, for their part, are encouraged to consider explaining what a preprint is, and what a peer review entails. They should provide a link to the preprint, they should not refer to it as ‘published’, and they should include details of the limitations of the study.

Uncertainty as part of the curriculum

Aysa Ekanger, an adviser at the University Library at UiT the Arctic University of Norway, thinks this is useful advice. She believes that researchers, the media, journals, research institutions and the school system all have a responsibility.

‘Research institutions should inform students and staff of methods for presenting uncertainty in research. Lower and upper secondary schools should teach pupils about the concept of scientific uncertainty. It is important that everyone understands what this is, and that researchers’ uncertainty about certain aspects does not mean that all of their research work is erroneous’, says Ekanger.

Ragnhild Ørstavik believes that future developments can go in several possible directions.

‘If more inaccurate results are spread, it can obviously weaken public confidence in research’, she says.

But she can also envision the opposite: a more transparent research process, constructive criticism that is taken on board, and the clear marking or removal of erroneous results.

‘This can lead to greater understanding of the scientific process and the long and often difficult road to what we can describe as certain and true. It all depends on future developments’, says Ørstavik.

Translated from Norwegian by Carole Hognestad, Akasie språktjenester AS.